In the Light of Angels

A journey through 12 masterpieces of the Uffizi Galleries, between human and divine

- 1/25Introduction

Angels have been one of the most frequent subjects in art of any period, and this is why they are so familiar in our shared imagination. They have accompanied us throughout our lives: from the angels in the fairy tales of our childhood and in traditional sayings, to their appearances in literature, music, and in more modern times, film. Who doesn’t remember Clarence, the angel, who on Christmas Eve saves the leading character from suicide in It’s a Wonderful Life by Frank Capra? The visual power of angels is such that they are now even a staple in Japanese manga, where they have become curious fantasy characters, somewhere between Christian tradition and extra-terrestrials.

If we want to see why there continues to be so much interest in angels, who are as fascinating as they are mysterious, we need to take a huge step back in time. The cult of angels has ancient roots, originating in the cultures of the Middle East, from the Babylonians to the Egyptians, both of which mention angels some centuries before they make their entry into Jewish thought. In the Old Testament, angels were identified with the word mal’ak, meaning ‘messenger’, a term that would later be used in the Koran, the holy text revealed to Muhammad by Archangel Gabriel after he was sent by God. Translated from the Greek word anghelos, which was used to refer to Hermes, the messenger of the Gods, the word began to enter the Christian faith, becoming established in almost every language today.

It is as messengers of God that we find many angels in the Old Testament. They appear in the Book of Genesis to sanction the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden or they rush in to stop Abraham seconds before he is about to sacrifice his son, Isaac. They also take the role of spirit guides, such as in the case of the young Tobias, escorted by the Archangel Raphael on his long journey to collect money on behalf of his father. In the New Testament too, angels had the task of connecting Heaven and Earth, of accompanying the life of Jesus and that of his family. An angel was sent to tell Mary of her pregnancy; a group of angels sang hymns of praise on the night that Christ was born, and again when the Magi arrived. Angels ministered to Jesus after the temptations suffered in the desert of Judea, and they waited for Mary Magdalene on the empty tomb to announce the Resurrection. They also surround the Virgin as she ascends into the heavens and the ministers on the Day of Judgement described in the Book of Revelation are angels. Myriad events at the root of the reflections of early Christian theologians on the nature and role of angels, and the codification of the orders that Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite brought together in his celestial hierarchy, from the Seraphim to the Cherubim - the closest to God and literally aflame with his love - to the archangels and the guardian angels, responsible for the destiny of humankind. However, aside from the voices of the Church Fathers, the affection found in popular tradition for some angels, such as Michael, the warrior who defeats the Devil, soon led to a need to portray them in some way. Angels needed to be made recognisable with their most distinctive feature, as evoked in the scriptures: their feathered wings. This characteristic was also used for many pagan divinities but was also useful for explaining the essence of these creatures, pure spirits midway between the heavens and at the same time, a profound part of human destiny here on earth. To this specific feature, the colour of which changes to distinguish the fact that they belong among the Seraphim (red wings) or the Cherubim (blue wings) we can add clothing details, such as long, precious robes, the details on their delicate, almost feminine faces, their musical instruments and their role as singers of the divine. The route, shown through HyperVisions, invites visitors to look at famous works as well as lesser known pieces from this special viewpoint. In each one, it will be possible to uncover the variations and iconographic choices used to portray angels, especially those around Mary’s throne in the grandiose Madonna Enthroned by Giotto, passing from the extremely delicate, blond youth who is approaching an almost terrified Mary in the Annunciation by Simone Martini, to arrive, after the enchanted heavens painted by Beato Angelico, at the interpretations by the Mannerists, from Rosso to Parmigianino, and by the major artists of 17th-century Florence. Every piece reveals a symbolic universe used by each artist to embody these enchanting messengers. This is a journey through Italian and European artworks, which brings together different periods while inviting us to take a deeper look at and appreciate ourselves as human beings.

- 2/25Giotto

Virgin and Child enthroned, surrounded by angels and saints (Ognissanti Maestà)

1310 - 1311 ca.

Tempera on wood, 325 x 204 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 2

Inv. 1890 n. 8344

Giotto lived in a pyramidal civilization [...], built architecturally, in which each individual was a stone and, when put together they formed a monumental society. Instead, we live in the midst of anarchic abandonment; artists like us, who are so fond of order and symmetry, are isolated.

Vincent Van Gogh, Lettres de Vincent Van Gogh à Émile Bernard.

The Dutch painter appears to be writing while admiring this work; he seems to be experiencing the contrast with his tormented feelings. "He created natural art and the gentleness that accompanied it, by not stepping outside the lines": many years before, Ghiberti had captured this same essence but, besides the rigor in the construction of space, he also noted the artist’s ability to give his subjects a physical and human consistency.

The Majesty is introduced by four angels, arranged on each side of the throne. One of them is holding a crown, a royal attribute, while the other holds a pyx, or a myrrh casket: both objects appear to allude to the human nature of Christ and, therefore, to his forthcoming sacrifice.

Artwork detailsVirgin and Child enthroned, surrounded by angels and saints (Ognissanti Maestà)Painting | The Uffizi - 3/25Giotto

The kneeling angels have different colors of wings - red and blue - perhaps revealing their dual nature, as Seraphs and Cherubs. They offer Mary vases full of flowers: the lilies and white roses evoke purity, while the red roses recall Charity and, in particular, a new prefiguration of Christ’s martyrdom. It should also be remembered that one of the names of the Madonna was “rose without thorns”: indeed it would appear that the roses in the Garden of Eden grew without thorns, and they were thus compared to the Virgin, born without any shadow of sin.

Artwork detailsVirgin and Child enthroned, surrounded by angels and saints (Ognissanti Maestà)Painting | The Uffizi - 4/25Simone Martini

Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus

1333

Tempera on wood, 184 x 210 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 3

Inv. 1890 n. 452

One moment

of universal coexistence,

of total evidence-

things enter

the mind that creates them, they enter

the name that calls them,

the miraculous coincidence blazes.

In that moment

- gold and lapis lazuli -

help me, Mary, I will engrave you

for your glory,

for the glory of heaven. So be it.

Mario Luzi, Viaggio terrestre e celeste di Simone Martini.

That moment of suspense spent waiting for Mary’s answer, when Eternity looks out on time. Surrounded by Seraph angels, the dove of God’s Holy Spirit swoops down; the Logos, the verb of John the Evangelist, becomes flesh, or, following the inverted rhythm of Luzi’s poem, "things enter the mind that creates them". Simone interprets the concept by placing the sentence pronounced by the angel in the center, with its characters written in pastille, in relief on the golden background of the panel.

Artwork detailsAnnunciation with St. Maxima and St. AnsanusPainting | The Uffizi - 5/25Simone Martini

The Archangel Gabriel is also floating in a moment. He has just ended his flight, his peacock feathered wings are still spread and his mantle is ruffled by one last force of wind.

With one hand, he points to the dove, while in the other he holds an olive tree branch, a message of peace meant to calm Mary’s worries. A little further beyond, on the limit between heaven and earth, between thoughts and things, lilies recall the purity of the Virgin, the universal coexistence of human and divine that occurs inside her.

Eternity thus enters history: for this reason, Florentines measured the years ab incarnatione and considered the 25th of March, the feast of Annunciation, the first day of the new year.

Artwork detailsAnnunciation with St. Maxima and St. AnsanusPainting | The Uffizi - 6/25Beato Angelico

Coronation of the Virgin

1431-1435

Tempera on wood, 112 x 114 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 7

Inv. 1890 n. 1612

Dress me in your wonderous tunics,

So rich and in such fine cloth,

Then pull me, dancing, into your round!

Simon of Cascina, Colloquio spirituale, c. 1380

Some forty angels are gathered around Mary and Jesus to celebrate a rite in which the onlooker can immediately perceive an atmosphere of pure beatitude. Traditionally, scenes of this type were known as “Paradiso” throughout the 16th century. Jesus is seated in the centre, facing his mother, and he is placing a last, precious jewel in her crown. The emotional intensity of this act is such that it holds the whole assembled group of angels and saints in thrall. This group includes St Giles, who is easily noticed by his light blue cloak and the church for which the panel was painted is named for him (Sant’Egidio). The angels form a single group, a point of contact between the human and the divine, divided according to their tasks.

A cloud of winged heads supports the two protagonists and their colour – blue like the cloak of the Virgin, tells us that they Cherubim, the angels who, by definition, are “beyond the throne of God” and therefore, the closest to him after the Seraphim, enflamed with love for the Lord and therefore, painted in red.

- 7/25Beato Angelico

Around a central group, six angels in robes of different colours, are dancing, accompanied by another thirty, singing and playing stringed and woodwind instruments. In the bottom of the painting, two angels are playing a portative organ and a rebec (a stringed instrument similar to a viola), while two more are spreading precious incense. They are carrying out one of the main functions that the Jewish mystical exegesis assigned them, i.e., to sing and dance in celebration of the Lord.

- 8/25Filippo Lippi

Coronation of the Virgin

1439 - 1447

Tempera on wood, 204 cm x 291,5 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 8

Inv. 1890 n. 8352

One all seraphic in ardour;

the other for wisdom was on earth,

a splendour of cherubic light.

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Paradiso, Canto XI

In these three lines, the great poet describes the two most important saints of his time, Francis and Domenic, using comparison with two spheres of angels. The arrangement of the Hierarchy of Angels, widespread in the Middle Ages and used by Dante in his Comedy, dates back to the 5th century. It was set out by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite in his De coelesti Hierarchia, where he talks of three hierarchies of angels, characterised in turn by three spheres of angels. Seraphim and Cherubim are the angels closest to God: the most important, with red wings, are burning with Charity like St Francis, while the others, shown with blue wings, embody the Knowledge of God, and are the guardians of divine attributes among humankind.

- 9/25Filippo Lippi

Seraphim and Cherubim are the most represented angels in art works of every period, and they can even be recognised among the close ranks of winged children that characterise the work of Filippo Lippi. Their presence on the large panel personifies and increases the meeting of divine and human that is taking place in the centre, where God the Father crowns Mary on her monumental throne. The lilies they hold aloft are a reference to divine incarnation, represented above in the Annunciation, and enhances the purity of the woman, the fact she is without sin, a human and divine character at the same time.

The artist too is a part of this praise for Mary: he painted himself dressed as a monk, gazing out towards the onlooker from behind St Ambrose.

- 10/25Andrea del Castagno

Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Jerome, angels and two children from the Pazzi family

1445-48

Detached fresco, 290 x 212 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Contini Bonacossi Collection, Room of Andrea del Castagno

Inv. Contini Bonacossi n.2

The scene occurs on one level, around the marble platform where the Madonna with blessing Baby Jesus is sitting. Next to her, the solid figures of Saints John the Baptist and Jerome stand out, while just behind them two angels leaning on the armrests of the throne are gazing at Mary. On either side of the throne, two people who really existed appear, the twins Renato and Oretta, the children of Piero d’Andrea Pazzi, commissioner of this work; they are carrying a vase and a garland of flowers as gifts. Young Renato is wearing a necklace representing the venture in the form of a vessel with the wind in its sail, given to his family by King René d’Anjou.

- 11/25Andrea del Castagno

At the top, on the two sides of the large disk - which is empty today, but originally may have contained a Heavenly Father or the family crest - two large angels swoop down for an audacious glimpse of the scene, holding up the ends of a drape of honor decorated with arabesques, in line with a taste the painter had studied during his stay in Venice. Their flight and the sumptuous cloth unraveled as far as the ground mark the boundaries between a sacred space, in the etymological sense of “separate”, and an undefined elsewhere, only hinted at by the ultramarine blue distance kept by the sky.

- 12/25Sandro Botticelli

Virgin and Child, and Angels (Madonna of the Magnificat)

1483 ca.

Tempera on wood, 118 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 10-14 of Botticelli

Inv. 1890 n. 1609

There are no less than five angels depicted by Botticelli in this very refined work: two, on the sides of the circle, are about to place a crown and an impalpable veil on the head of the Virgin Mary; another two, in the foreground, are sitting next to the Madonna, helping her write a canticle. One is holding the book for her and the other one is holding out the inkwell for her to dip the pen into. The third angel, standing, holds the other two in an embrace.

Artwork detailsVirgin and Child, and Angels (Madonna of the Magnificat)Painting | The Uffizi - 13/25Sandro Botticelli

The angels are five young men with beautiful features, without wings; they are wearing preciously woven, richly decorated clothes and their hair is styled in the fashion of the late fifteenth-century. They resemble the young men of the Florentine aristocracy with whom Sandro would keep company and their portraits help build that model of refined beauty that has made Botticelli so famous and greatly admired by visitors throughout the world, to this day.

Artwork detailsVirgin and Child, and Angels (Madonna of the Magnificat)Painting | The Uffizi - 14/25Andrea del Verrocchio e Leonardo da Vinci

The Baptism of Christ

1475 ca.

Tempera and oil on wood, 177 x 151 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 35

Inv. 1890 n. 8358

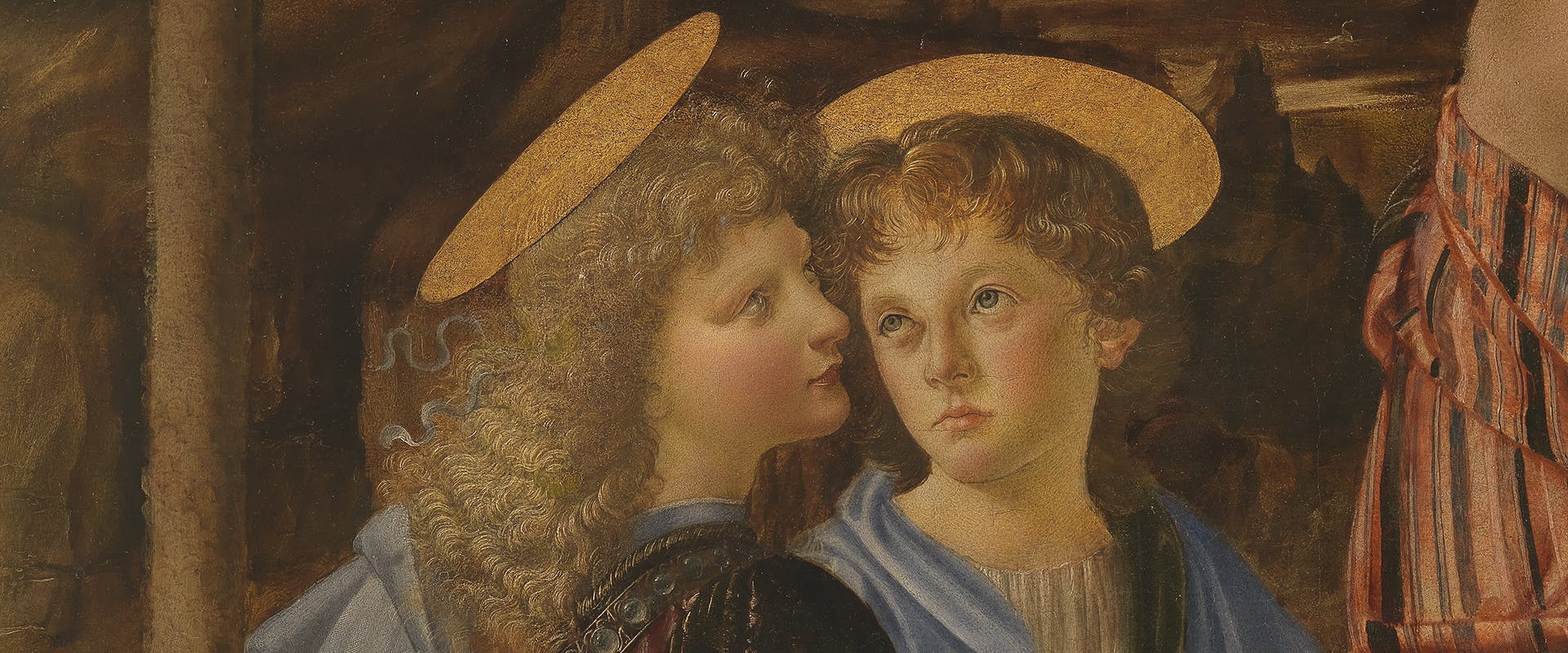

Two kneeling angels watch the scene of the Baptism of Christ. Of the various students said to have collaborated in the making of this work in the workshop of the Master Verrocchio, sources point in particular to a young Leonardo da Vinci, who provided extraordinary and precocious proof of his talent in the angel on the left.

Artwork detailsThe Baptism of ChristPainting | The Uffizi - 15/25Andrea del Verrocchio e Leonardo da Vinci

The figure is depicted in its vibrant essence as it is constructed from several viewpoints with a refined use of the sfumato technique. The angel is wearing a light blue mantle animated in an extraordinary effect created by the folds, but outlines the anatomy of his adolescent body; he is facing towards the right, contemplating Christ as the future Savior while holding his gown. In his face, with its exceptionally soft, bright complexion and his soft, blond, vaporous hair, slightly swayed by a subtle breeze, Leonardo truly anticipates those “motions of the soul” that would characterize his production so deeply and mark many painters after him.

This creature truly embodies the spiritual and divine dimension, in contrast with the earthly one, represented by the angel on the right: another very sweet young boy, gazing at his friend beside him with brotherly love.

Artwork detailsThe Baptism of ChristPainting | The Uffizi - 16/25Rosso Fiorentino

Angel playing the lute

1521

Oil on wood, 39 x 47 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 60

Inv. 1890 n. 1505

For a long time, this small panel was considered a standalone work; in fact only recently a restoration procedure revealed that it is actually a fragment of a lost altarpiece; it originally featured a Sacred Conversation by Francesco Vanni (about 1600), kept in Saint Agatha’s Church in Asciano. According to a tradition that was widespread in Italy during the 16th century, the little angel was sitting at the feet of a throne occupied by the Madonna holding the Holy Child in her arms.

Artwork detailsAngel playing the lutePainting | The Uffizi - 17/25Rosso Fiorentino

The young boy is depicted playing a lute, which appears enormous compared to his minute dimensions: he has his ear pressed against the sounding board to hear the best sound, his gaze is focused on his left hand, while his right hand is plucking the chords. The graceful interweaving of his copper-colored locks of hair and the high level of lyricism in this modern and poetic reinterpretation of a traditional theme make the work one of the icons of the 16th century in Florence.

Artwork detailsAngel playing the lutePainting | The Uffizi - 18/25Parmigianino

Madonna with Child, angels and a prophet (Madonna with the Long Neck)

1534 - 1540

Oil on wood, 132,5 x 216,5 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 74

Inv. Palatina n. 230

This extraordinary work has many complex symbolic meanings; a pure manifesto of Italian Mannerism, even though Parmigianino never finished it; this fact makes it even more difficult to provide a single, definitive interpretation.

On Mary’s left, a group of extremely refined ephebic figures strain to see Baby Jesus. How many of these angelic blond creatures are present? We must look very carefully to see that there are no less than six of them: a small head, it too unfinished by the painter, is in fact hidden under Mary’s right arm.

- 19/25Parmigianino

In the foreground, we see the full length figure of an angel, with one gray wing stretched upwards and revealing a very long, bare tapering leg, a precise reference to Saint John the Baptist in the Madonna with Saint George by Correggio. A possible key to the interpretation of this painting is offered by the particular iconography of this figure. Indeed, one of the angels is holding out a vase bathed in light to the Virgin. In the light, we glimpse a golden crucifix: this is a reference to the Immaculate Conception of Mary (and to the order of the “Serviti” Fathers, the owners of the church who had commissioned the painting). The Virgin Mary is therefore smiling as, already at the moment of the Conception, she foreshadows the Passion, death, but also Resurrection of Christ, already in her womb (Vas Mariae) and now a Child between her arms.

- 20/25Giovanni Bilivert

The Archangel Raphael refuses Tobias's gifts

1612

Oil on canvas, 175 x 146 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Pitti Palace, Palatine Gallery, Iliad Room

Inv. 1912 n. 202

The painting portrays the final episode of Tobias's Book, where the Archangel Raphael reveals his supernatural essence, refusing the gifts of Tobias and his father. The archangel had accompanied Tobias on an adventurous journey under false pretenses, during which he had helped him catch a large fish, from which he would then extract the medicine needed to cure Tobias’s blindness and the curse cast on Sarah, his wife, by the demon Asmodeus.

The observer is drawn in and captivated in a hypnotic circle by the interplay between the triangle of gazes, and that of the hands, which embodies the synthesis of contrasting feelings in a single moment. With his hands, Tobias holds on, and gratefully offers his most precious gifts. Instead, with his eyes, he incredulously looks on as Raphael’s revelation reveals the archangel’s true nature, while the old father seems to hesitate, seeking reassurance in his face. The dialog is amplified by the meticulous attention to the portrayal of the details and, in the background, by the conversation between Sarah and Anne, the elderly mother.

- 21/25Giovanni Bilivert

Angels can also be seen in the sumptuous Baroque frame of this painting. In fact, throughout the 17th century, the frames defined as “subject frames” became hugely popular with the Medici: they were characterized by the presence of iconographic elements that made clear references to the painting they hosted.

- 22/25Botticini Francesco

Tobias and the three Archangels

1467 ca.

Oil on wood, 134 x 153 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 15

Inv. 1890 n. 8359

While Bilivert chooses to paint a relatively unusual scene, namely the moment when Raphael refused the gifts he was being offered, Botticini portrays Tobias accompanied by the angel and the miraculous fish. This iconography had already been widespread since the 15th century, and it had become the ultimate representation of the popular devotion reserved to the figure of the Guardian Angel. In Florence, the latter had led to the creation of the Fellowship of the Archangel Raphael, which had a chapel in S. Spirito from 1455 on; this was the chapel for which Botticini’s painting was created.

Raphael is therefore the angel that guards, the one that holds hands and cures wounds, as the jar of medicine he is showing would appear to indicate. By the sides of the two protagonists, the painter also depicts the other archangels quoted in the Scriptures, Michael and Gabriel, also characterized by splendid wings, an iconographic element borrowed from the Winged victory of the classical world.

- 23/25Francesco Botticini

Michael, great prince of the heavenly armies, fighting Satan and alienating Rebel Angels, is wearing a sparkling warrior armor while holding the sword of victory up high. Here, he also holds a sphere; in other representations he holds the scales he uses to weigh souls before the Last Judgment.

Lastly, Gabriel is the ultimate messenger angel; he is depicted carrying the lily he offered to Mary in the Annunciation.

- 24/25Giovanni da San Giovanni

Christ served by angels

1625 - 1630

Oil on copper, 35 x 42.5 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Pitti Palace, Palatine Gallery, Room of Allegories

The episode is taken from the Gospels of Matthew (4:11) and Mark (1:13). Jesus, emerging victoriously from the battle with satanic temptations in the desert, is fondly comforted by a multitude of angels.

We can count no less than seven of them and their number is not entirely coincidental: although in the Bible the names of only three angels appear (Michael, Gabriel and Raphael), the Book of Enoch, an apocryphal text from the 1st century BC, also mentions Uriel, Saraqael, Raguel and Ramiel. The early Church was faced with various problems linked to the cult of angels, often associated with idolatry practices and in the nineteenth century, the Church outlawed the veneration of the angels not mentioned in the Bible. Despite this, a few heterodox representations managed to survive this censorship in popular devotion and in sacred art.

- 25/25Giovanni da San Giovanni

This small panel by Giovanni da San Giovanni is probably without complex iconographic implications, but its original location in the private apartments of the grand-ducal family makes it an object of personal devotion and could therefore justify the presence of the seven Archangels in their functions of support and comfort, which was not a typical practice.

In the Light of Angels

Credits

Scientific Coordinator: Anna Bisceglia

Texts: Andrea Biotti, Anna Bisceglia, Noemi Gaglio, Francesca Sborgi

Translations: Eurotrad Snc.

Editing by Dipartiment of Digital Strategies - Gallerie degli Uffizi

Published December 2019

Please note: each image in this virtual tour may be enlarged for more detailed viewing.