The Princes' Fragile Treasures. The Paths of Porcelain between Vienna and Florence

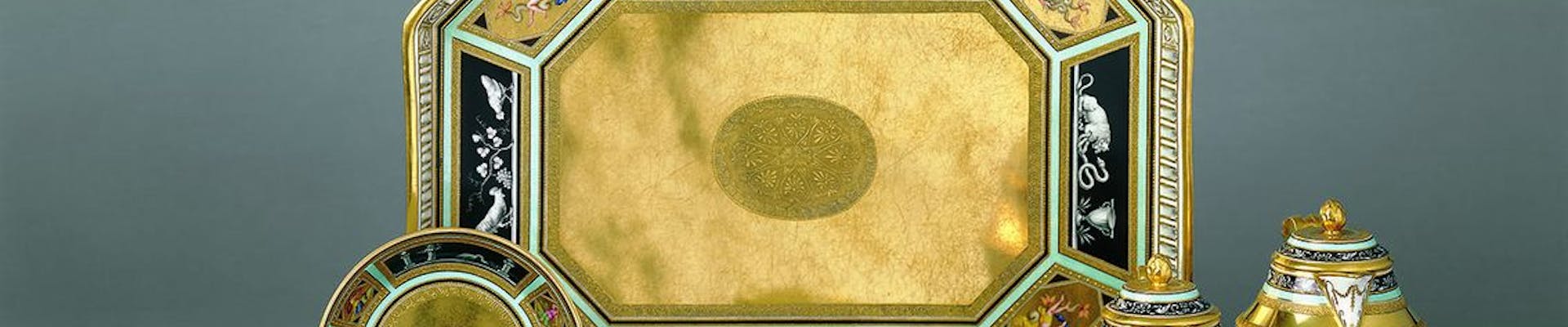

Porcelain, but also paintings, sculptures, semi-precious stone inlay work, ivory, crystal, tapestries and engravings serve to point up the fertile dialogue among the arts, celebrating the magnificence of porcelain in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany during the rule of the House of Lorraine.

When Count Carlo Ginori summoned Carlo Wendelin Anreiter de Ziernfeld, an Austrian painter specialising in the decoration of porcelain, to his service in 1737, money was clearly no object. A document of the time tells us that “… he [Ginori] is obliged to bring him to Tuscany with his Wife and Children, at his expense, and there to pay him Florins 600 per annum, also providing lodgings for him and for his family, and board and wine for said Ziernfeld alone, and to continue thus with such provision for a period of six years”.

In short, that generous salary plus board (with wine!) and lodging for him, for his wife and for his 10 children, plus 3 more who were born while the couple were in Italy, served to allow Ginori to acquire the services of the best artist in his field on the European marketplace. Ginori clearly wished his manufactory in Sesto Fiorentino to achieve the highest quality in the shortest time possible, while at the same time forging a very close bond with the Vienna manufactory founded by Claudius Innocentius Du Paquier in 1718. The result was that both manufactories' output ended up playing a crucial role in the dissemination of the decorative motifs, forms and artistic techniques that were to forge the dominant taste and style of the period.

All of this and much more is the focus of an exhibition entitled The Princes' Fragile Treasures. The Paths of Porcelain between Vienna and Florence, curated by Rita Balleri, Andreina d'Agliano and Claudia Lehner-Jobst and produced in conjunction with the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein (Vaduz–Vienna).

The works on display – porcelain of course, but also paintings, sculptures, semi-precious stone inlay work, ivory, crystal, tapestries and engravings – serve to point up the fertile dialogue among the arts, celebrating the magnificence of porcelain in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany during the rule of the House of Lorraine. The exhibition showcases loans from national and international institutions, from leading museums in Europe and the United States and from a number of important private collections.

The entrepreneurial energy of the Marquis Ginori, a Florentine Senator, spanned broad horizons, and the porcelain he manufactured reveals an international taste that could encompass the Florentine tradition while at the same time being open to influence from the Far East, in particular from China, in his determination to meet the needs of his demanding patrons both in Italy and abroad. If the manufactory was to prosper, it had to be open to all the innovations pouring in from elsewhere, and so the artistic climate and output both in Doccia proper and in the rest of Florence under the House of Lorraine were inspired by a criterion of cosmopolitan excellence. Porcelain was no exception, for it not only mirrored the experiments taking place in other artistic spheres but also reflected a vast range of social customs and fashions at a time of great change, including in people's eating habits. The Medici were the first to develop a taste for chocolate, importing it from Spain in 1663, and it was love at first sight. But as Gallerie degli Uffizi Director Eike Schmidt points out in the exhibition catalogue, the consumption of chocolate and coffee “required the creation of new objects and new tableware, which we can almost hear chinking and glimmering in the splendour of the Kaffeehaus built in the Boboli Garden to a design by Zanobi del Rosso and completed in around 1785 (and, we would add, soon due to reopen after an in-depth restoration campaign). Another architectural jewel commissioned by Pietro Leopoldo, its bulging roundness revealing the influence of Viennese Rococo, it is of course a brick and limewash construction, yet from afar it has the appearance of a fancy porcelain item from Doccia, almost a giant cup with a dome for a lid”.

“European cooperation and thought crossing national boundaries – explains Johann Kräftner, Director of the LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna – are manifest in the history of the two manufactories which share a common history of governance and collecting that comes together in this exhibition, a product of the current cooperation between the two institutions and their staff. The exhibition traces the path of this long story not in Vienna, where it has already been explored in an exhibition entitled Barocker Luxus Porzellan in 2005, but in Florence, where the ideas found a common and very fertile terrain”.