New languages to communicate tradition: Vanished Florence

Images of the city in the 18th and 19th centuries, before it became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy.

- 1/23Richa – Frontispiece

G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’ suoi quartieri, Florence, Gaetano Viviani print house, 1754-1762, 10 volumes (anastatic reprint, Rome, Multigrafica, 1972).

- 2/23Richa – Portrait of Richa

The extensive work in 10 volumes was written by Giuseppe Richa, Jesuit priest from Turin and learned researcher of notable information on the history of Florentine churches, who was well known to many of his contemporaries. It included numerous prints that today are precious evidence of some of the Florentine famous sites over the 18th century.

- 3/23Demidoff – Frontispiece

La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque exécuté sous la direction de M. le Prince Anatole Demidoff, dessiné d’après nature par André Durand, avec la collaboration d’Eugène Ciceri, Paris, Lemercier, 1862 (reprint, Florence, Cassa di Risparmio, 1973).

- 4/23Demidoff – Portrait

Well-known benefactor of the city, Anatoly Demidoff, honoured with the title of “Prince of San Donato” at the wishes of the Grand Duke, promoted this interesting publishing initiative in 1862, three years before Florence became the capital of the new Kingdom of Italy. Demidoff appointed André Durand, a gifted lithographer, to depict the most charming locations in Tuscany’s main cities. Of these, we have chosen some rare images of Florence in the 19th century, as it was just a little before the urban development carried out by Giuseppe Poggi.

- 5/23Church of Santa Croce (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol. I)

Compared to the modern-day square, the front of the church is still bare and without the marble covering we are used to seeing, which was the work of architect Nicolò Matas a century later, between 1853 and 1863. We can also note the differences in the buildings around the square and the absence of the monument to Dante Alighieri, which today is situated in front of the church and was sculpted by Enrico Pazzi on the occasion of the 600th anniversary of the poet’s birth. The monument to Dante was inaugurated in May 1865, with an important ceremony attended by King Victor Emmanuel II. The event was celebrated on national scale because this was the first celebration for the Kingdom of Italy and it was held in Florence, chosen as the capital of the Kingdom just a few months beforehand.

Bibliography: E. Pucci, Com’era Firenze 100 anni fa, Firenze Bonechi, 1969; P. Aranguren, Le feste per il Centenario (1865) della nascita di Dante in Firenze capitale, estratto da “La Martinella”, 1965.

- 6/23Ponte di Rubaconte (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol. I)

This image is of the old Ponte alle Grazie, a bridge previously known as “Ponte di Rubaconte”, in memory of its founder, Podestà Rubaconte da Mandello from Milan, who ordered to build the bridge in 1237. Small chapels and hermitages were built on the pillars of the bridge; these were used to house nuns, at least until the River Arno flooded in 1558. The name of the bridge was changed into “Ponte alle Grazie” towards the mid-14th century, when Jacopo degli Alberti commissioned a church there in honour of Our Lady of Graces. The bridge was destroyed by retreating Nazi troops in August 1944, along with other Florentine bridges (except for Ponte Vecchio), and it was rebuilt – and renamed – in 1957.

Bibliography: G.Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, divise ne’ suoi quartieri, in Firenze, nella stamperia di Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1972), vol. IV; E. Pucci, Com’era Firenze 100 anni fa, Firenze Bonechi, 1969; P. Bargellini, I ponti di Firenze, Firenze, Istituto professionale Leonardo da Vinci, 1963.

- 7/23Triumphal Arch of the Lorraine (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol. I)

The Triumphal Arch of the Lorraine was erected to celebrate the arrival in Florence of the new Grand Duke from the Habsburg-Lorraine family, Francis Stephen, who became the new ruler of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in 1739, after the end of the Medici dynasty. It was presented by Richa as a new monument to embellish the city in the mid-18th century. In the topography of the period, the arch was outside a gate in the old city walls, known as “Porta San Gallo”. The site was completely redesigned by architect Giuseppe Poggi after 1865 and took the shape of the current Piazza della Libertà, where the ancient “Porta San Gallo” gate can be admired today, still together with the Triumphal Arch, dedicated to the Lorraine Grand Duke.

Bibliography: G.Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, divise ne’ suoi quartieri, in Firenze, nella stamperia di Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1972), vol I; G. Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, 1897 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1985).

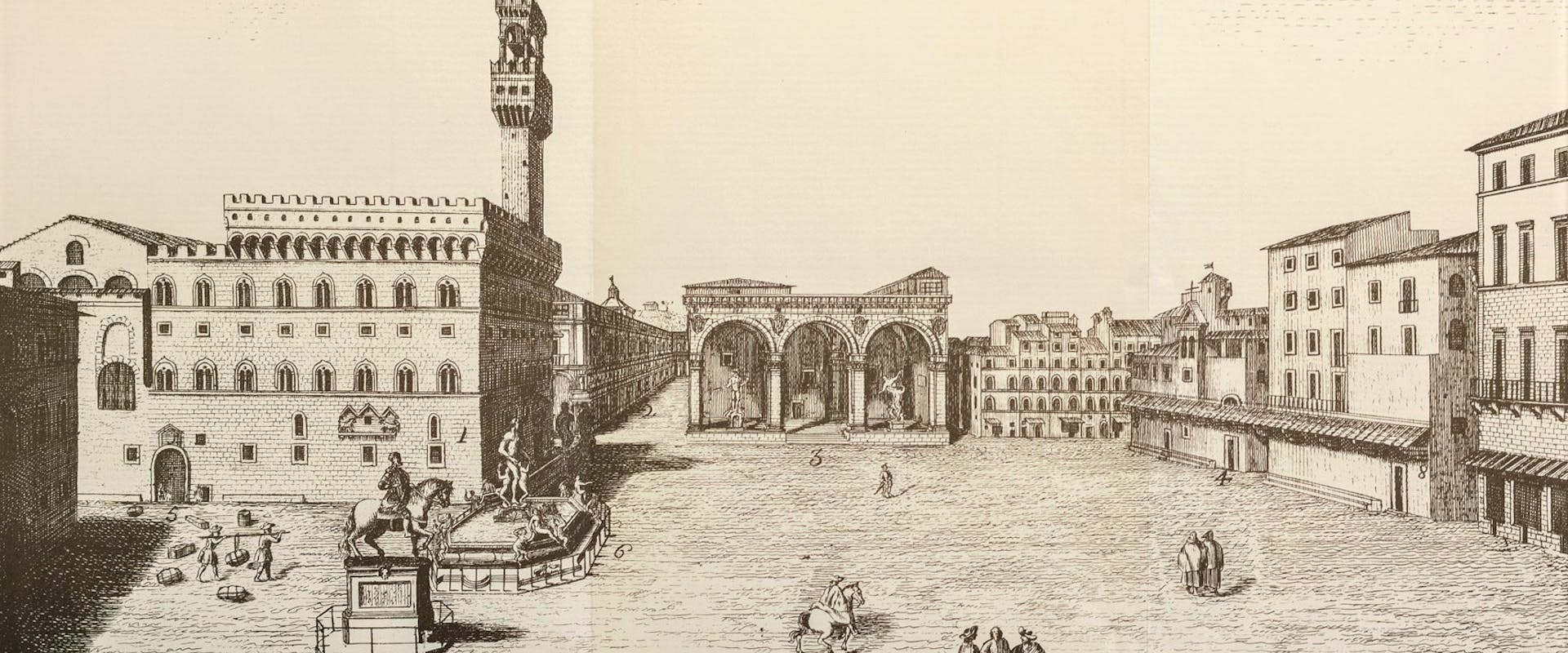

- 8/23View of Palazzo Vecchio (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol. II)

This “View of Palazzo Vecchio” in the 18th century shows an unusually bare Loggia dei Lanzi, without a vast part of the sculptures we usual admire there. In fact, some of the large marble sculptures, like the Sabine Women and the Lions, were transported there from Villa Medici in Rome, at the orders of the Grand Duke, Peter Leopold of Tuscany, only between 1787 and 1791. Worthy of note is the position of the Customhouse door that stood next to Palazzo Vecchio in the 18th century. This is where anyone wishing to enter the city with their wares would have to pay duties. It is also possible to note the so-called “Tetto dei Pisani” opposite Palazzo Vecchio: a canopy erected by Pisan soldiers imprisoned by the Florentine army and taken to Florence after the battle of Cascina, occurred on the 29th of July 1364. This ancient testament to the mediaeval wars between Florence and Pisa was destroyed during the urban development works carried out by Giuseppe Poggi to turn Florence into a capital city.

Bibliography: F. Vossilla, La Loggia della Signoria: una galleria di scultura, Firenze, Medicea, 1995; G. Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, 1897 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1985); G.Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, divise ne’ suoi quartieri, in Firenze, nella stamperia di Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1972), vol III.

- 9/23View of Piazza S. Maria Novella (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol.III)

In Piazza Santa Maria Novella, on the day before the festivities for the Patron Saint, that is St. John the Baptist (24 June), the “Palio dei Cocchi” horserace would be run, which went on for about three centuries, with just a few exceptions. It was inspired by the old Roman chariot races and was introduced by Cosimo I in 1563. To mark the points where bends were to be negotiated, two wooden pyramids were built: one opposite the front of the church, the other on the side with the loggia of the old church of San Paolo. A strong rope was stretched between the two pyramids to force the race to take an oval route and to prevent the drivers from cutting across the track. After three laps around the pyramids, completed thanks to the “tactical” skills of the drivers, the race finished at the starting pyramid. The winner would be rewarded with a crimson-red velvet flag, which would be flown from the top of the pyramid on the side of the facade. Ferdinand I had the wooden pyramids replaced with two obelisks in mixed marble from Seravezza, standing on 4 bronze turtles by Giambologna.

Bibliography: L. Artusi - S. Gabbrielli , Feste e giochi a Firenze, Firenze, Becocci, 1976

- 10/23Corsa de’ Barberi (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol. IV)

The race of “Barberi” horses (i.e. of “Berber” breed) would traditionally take place during the celebrations in honour of St. John (24 June). The first records date back to 1288, in a description by Giovanni Villani in his Chronicle. The splendid “palio” flag was trailed through the city streets and then taken to Piazza San Pier Maggiore, where it marked the end of the race, known as the “ripresa” or “riparata”. The “mossa” (start) was on the Mugnone bridge (now known as Ponte alle Mosse) at the third ring of the bell in the Torre d’Arnolfo. The mad route of the “barbari scossi”, horses without a jockey, would cross the Porta al Prato gate, Borgo Ognissanti, Via della Vigna Nuova, Mercato Vecchio (now Piazza della Repubblica), Via del Corso (hence the name), and Borgo degli Albizi, ending at the “riparata”. The last “Barbari” race took place in 1858, shortly before the last Grand Duke of Tuscany left Florence foreveBibliografia: L. Artusi, Feste e giochi a Firenze, Firenze, Becocci, 1976; G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, diuise ne' suoi quartieri, Firenze, Nella stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1972), vol IV. r.

Bibliography: L. Artusi, Feste e giochi a Firenze, Firenze, Becocci, 1976; G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, diuise ne' suoi quartieri, Firenze, Nella stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1972), vol IV.

- 11/23The Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche… cit., vol. VI)

This engraving shows the Piazza del Duomo as it was in the 18th century. It also offers us a singular view of the front of the Cathedral. In 1668, on occasion of the marriage between Grand Prince Ferdinand, Cosimo III commissioned a company from Bologna to plaster and paint the bare front of the Cathedral, according to a design by Ercole Graziani. The decoration visible in the mid-18th century was embellished with three large panels on the doors, depicting the three Ecumenical Councils celebrated in Florence. “Over the middle oculus” was the “coat of arms of the Grand Dukes”, flanked by the figures of Charity and Religion. The faded traces of paintwork on the Corinthian-style architecture, still recognisable in 19th-century photographs, were removed in 1871 when works on the modern-day facade (completed in 1887) were begun.

Bibliography: F. Gurrieri [a cura di], La cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore a Firenze, Firenze 1994-1995, vol. I; G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, divise ne' suoi quartieri, Firenze, Nella stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1972), vol VI.

- 12/23Richa – View of Piazza San Marco (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche…cit., vol. VII)

In this 18th-century image, the square is of a size that we are unused to seeing, with, in the background, the clear outline of the old church and convent of San Marco, as it was before 1780, when Friar Gioacchino Ponti renovated the front, giving it its sober Baroque style. Today, the centre of the square hosts the monument to General Manfredo Fanti, cast in bronze by sculptor Clemente Papi in 1872, surrounded by a series of flowerbeds that serve to restrict the space in front of the old 15th-century Dominican convent.

Bibliography: Firenze: guida per il viaggiatore curioso, Firenze, Mandragora, 1998.

- 13/23Richa – Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova (from G. Richa, Notizie istoriche…cit., vol. VIII)

Founded by the private charity of Folco Portinari, father of Dante’s beloved Beatrice, at the end of the 13th century, the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova is one of Florence’s oldest buildings. This 18th-century image brings out the full beauty of the loggia that borders the rectangular space in front of the hospital, built from designs by Bernardo Buontalenti (1531-1608), at different stages in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Bibliography: F. Brasioli, L. Ciuccetti, Santa Maria Nuova: il tesoro dell’arte nell’antico ospedale fiorentino, Firenze, Becocci, 1989.

- 14/23Demidoff – View of Florence (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

This is the view of Florence from above that we are traditionally used to seeing from Piazzale Michelangelo, but before the square was built by Giuseppe Poggi in around 1875, within the panoramic route of Viale dei Colli. The position of the square was chosen by Poggi through a careful examination of the land registry maps and many visits to the farms on the hill where the mediaeval church of San Miniato used to stand, the same viewpoint chosen by the author of this stupendous image.

Bibliography: Firenze: guida per il viaggiatore curioso, Firenze, Mandragora, 1998; C. Paolini, Il sistema del verde. Il Viale dei Colli e la Firenze di Giuseppe Poggi nell’Europa dell’Ottocento, Firenze, Polistampa, 2004.

- 15/23Demidoff – Ponte Santa Trinita (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

The history of the Santa Trinita bridge goes back centuries through the life of Florence. It was the first bridge to link the two banks of the Arno and was realized in wood by the Frescobaldi family in 1252. It was demolished more than once by the floods of the Arno and later built in marble, standing until 1557, when a devastating flood destroyed it. Ammannati was commissioned to rebuild it, but the works took ten years to commence and were not completed until 1570. The new Santa Trinita bridge was an absolute work of art. In 1608, four allegorical statues depicting the four seasons were added to the bridge. The bombing of the 4th August 1944 destroyed this precious bridge, which was only rebuilt in 1958, according to the original designs of Ammannati, replacing the recovered statues of the four seasons. The recovery of the missing head of the Spring is a well-known story. It only came to light in 1961 after a campaign launched by Parker, who offered a reward for its recovery. This initiative, which was widely publicised in the newspapers, is recorded in the Uffizi Library, in an album containing photographs and newspaper clippings.

Bibliography: P. Paoletti, Il Ponte a santa Trinita. Com’era e dov’era, Firenze, Becocci,1987; C. L. Ragghianti, Ponte a S. Trinita, Firenze, Vallecchi, 1948.

- 16/23Demidoff – Piazza S. Trinita (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

A woman with a small dog and a “puffed” skirt, a little beggar, a man in an overcoat and a wide-brimmed hat... These and other figures are in the Piazza Santa Trinita, around the granite column of Justice (from the Roman Baths of Caracalla, and topped by an allegorical statue). Three carriages are waiting in the shadow of Palazzo Spini-Feroni, built in the 13th century but renovated on more than one occasion: while Florence was the capital, it was adapted to become the City Hall and later restored to its Medieval style. The elegant Via de’ Tornabuoni leads onto this square; it was once Via Larga dei Legnaiuoli, also known as Stradone di S. Trinita according to Guido Carocci, and home to feasts, celebrations, rides and amusements. It is the setting of one of the Stories of St. Francis, painted in the Church of Santa Trinita by Domenico Ghirlandaio between 1483 and 1486: the miracle of resuscitating a dead child (showing the bridge before its collapse in 1557), the fatal fall of a child from a window in Palazzo Spini and the front of the church (still in its Gothic style, before the renovation by Bernardo Buontalenti).

Bibliography: G. Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, 1897 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica Editrice, 1985; Firenze. Guida per il viaggiatore curioso, Firenze, La Mandragora, 1998; Firenze e provincia, Milano, Touring Club Italiano, 2005.

- 17/23Demidoff – Ponte Vecchio (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

What is striking about this view of Ponte Vecchio is the presence of three small windows at the same height of the central arches of Vasari’s Corridor. In their place, today there are far more important openings, which allow enjoying a panorama over the Santa Trinita Bridge from the inside. The openings were made on the occasion of a visit by King Victor Emmanuel II shortly before the Unification of Italy. They were modified again after 1866, when the Corridor was opened for the public to use. The openings were then definitively restored to their current shape after the Second World War. As can be seen from the 19th-century image, the west side of the bridge still did not have the monument dedicated to Benvenuto Cellini, which was inaugurated in 1901 for the 400th anniversary of his birth, commissioned and wholly paid for by the Committee of artisan goldsmiths of Florence. On the roof alongside the shop on the left, it is possible to see the oldest sundials still working in Florence – from the late Middle Ages – which was placed on the bridge after it was rebuilt following the flood in 1333.

Bibliography: C. Paolini, Ponte Vecchio di pietra e di calcina, Firenze, Polistampa, 2012; S.Barbolini, G. Garofalo, Le meridiane storiche fiorentine, Firenze, Polistampa, 2011; Cristina Acidini, Le arti per l’assolutismo mediceo, in Vasari, gli Uffizi e il Duca, Firenze, Giunti, 2011.

- 18/23Demidoff – Church of Santa Maria Novella (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

Two monks are chatting in the vast square, which was built in the late 13th century to welcome worshippers during the Dominicans’ sermons. From the beginning of 1458, the church front was completed from designs by Leon Battista Alberti: the shining sun on the tympanum is the emblem of the Dominican order. The sails of fortune, billowing in the wind, glide across the marble (personal coat of arms of Giovanni Rucellai, who financed the work). The double volutes in inlaid marble on the sides of the top order are among the most inspired of Alberti’s inventions and bring together the two registers of the facade, hiding the pitched roof on the minor naves. This image shows the decoration on the volute on the right as unfinished: it was only completed in 1920 (a gap shown in a photo by Alinari in a volume of the Biblioteca d’arte illustrata in 1923).

Bibliography: Leon Battista Alberti, a cura di A. Venturi, Roma, Società editrice d’arte illustrata, 1923; S. Orlandi O. P., S. Maria Novella e i suoi chiostri monumentali, Firenze, Il Rosario, 1956; Santa Maria Novella, a cura di A. De Marchi, Firenze, Mandragora, 2015-16.

- 19/23Demidoff – Apse of the Church of Santa Croce (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

This view is the apse of the Church of Santa Croce. The unusual viewpoint offered is from the outside area to the back of the Franciscan building, where it is possible to admire the charming effect created by the upward movement of the gothic arches, which are dozens of metres high. This building is the oldest part of the church, which was begun in 1295, starting with the apse and the chapels in the transept, while the bell tower was designed and built later, by architect Gaetano Baccani, in 19th-century gothic style in 1842. The outside area, which only a few years previously has been isolated from the adjacent flower and vegetable gardens, seems well maintained and contains flourishing plants and shrubs. During the 20th century, this part of the building was left neglected until 1994, when it was restored.

Bibliography: L. Sebregondi, Santa Croce sotterranea, trasformazioni e restauri, Firenze, Città di vita,1997; Opera di Santa Croce, La sistemazione del resede absidale di Santa Croce, Firenze, Città di vita, 1994; F. Rossi, Arte italiana in Santa Croce, Firenze, G. Barbera. 1962.

- 20/23Demidoff – Porta San Gallo (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

In this rare image from 1862, Porta San Gallo is shown together with part of the last circle of city walls that was demolished as part of the urban development of Florence as capital city, by Giuseppe Poggi, after 1865, to make room for major traffic routes. Today, the old Porta San Gallo stands alone, in the centre of the new square designed by Poggi (now Piazza della Libertà), in front of the Triumphal Arch dedicated to Francis Stephen of Lorraine. The last circle of walls was the sixth, in chronological order, and was built between the end of the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century. Poggi did not destroy all of it: there is still a long section in the urban route from Porta San Frediano to Porta Romana, in the area known as “Oltrarno”.

Bibliography: G. Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, 1897 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1985); R. Manetti, M. C. Pozzana, Firenze: le porte dell’ultima cerchia di mura, Firenze, CLUSF, 1979.

- 21/23Demidoff – Porta San Niccolò (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

This image of Porta di San Niccolò shows us the gate, which we are now used to seeing on its own in the middle of the square, as a solid part of the old city walls that ran as far as the Arno. The weir in San Niccolò area was very busy over previous centuries: it was here that the old watermills powered by the river were located and which since 1572 had been the source to power the Zecca Vecchia (Old Mint) on the opposite side of the river, administered the very rich Arte del Cambio (Bankers’ Guild). These walls were demolished to make way for the new Lungarno Serristori, which, in Poggi’s project, allowed extending the panoramic walk along the banks of the Arno.

Bibliography: G. Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, 1897 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1985).

- 22/23Demidoff – Piazza San Firenze and the palace called “Bargello” (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

This image of the Bargello highlights, among other things, the putlog holes. A curiosity that perhaps not everyone notes: the “putlog holes” were holes made during the construction of a building, especially during the Middle Ages, and their purpose was to support - by means of poles placed between the stones - scaffolding used to complete particularly tall buildings. These poles could be removed at the end of construction and, in this case, they left holes behind them or - as is often the case in “tower-houses” - they could be stabilised at the base with a stone bracket supporting the beams of external platforms (ancestors of the modern balcony) that could also connect “tower-houses” belonging to the same guild. Towers had no doors and, therefore, could be entered through the windows with wooden ladders that would be pulled up to make the towers inaccessible. The putlog holes, which can still be seen in some Medieval buildings, were mainly filled in, above all during the Renaissance, to meet the new decorative requirements on facades and external walls.

Bibliography: Guido Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze 1897 (ristampa anastatica. Roma, Multigrafica, 1985).

- 23/23Demidoff – Palazzo Vecchio (from Anatoly Demidoff, La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, 1862)

Piazza della Signoria is captured from a side coinciding more or less where it meets Via dei Calzaiuoli, which, following the enlargement works started in 1842, had become a privileged road connection between the places of power: civil (Palazzo Vecchio) and religious (Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore) inside the Grand Duchy’s capital. Missing from the Loggia dei Lanzi as seen today are the group of Judith and Holofernes, there from 1504 to 1917, in different positions, underneath the archs. The same 13th-century portico had, at the wishes of Peter Leopold, housed the two lions and six ancient matrons from the Villa Medici in Rome, in 1791. In 1841, the collection of outdoor sculptures was extended with Hercules and Nessus by Giambologna and the ancient group of Menelaus and Patroclus. Three years after the vote to annex to the Kingdom of Italy, the coat of arms of the ancient Medici dynasty was still on the facade of Palazzo Vecchio, or perhaps just in our image.

Bibliography: C. Francini, Palazzo Vecchio. Officina di opere e di ingegni, Cinisello Balsamo 2006; Guido Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze 1897 (ristampa anastatica. Roma, Multigrafica, 1985).

New languages to communicate tradition: Vanished Florence

Introduction

On the occasion of the International Museum Day 2019 focused on "The future of tradition", the Uffizi Library offers its contribution by bringing two sources of exceptional interest to the attention of art enthusiasts. These document the image of the centre of Florence between the 18th and 19th centuries: Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’ suoi quartieri by Father Giuseppe Richa, published in Florence in 10 volumes, from 1754 to 1762, and La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque, containing a collection of engravings of the most charming views of towns and cities in Tuscany, promoted and published at the expense of Anatoly Demidoff, Prince of San Donato and well-known benefactor of the city, in 1862. This was the period preceding a number of important urban development works carried out by architect Giuseppe Poggi, who transformed the image of the old city in just a few years, updating its still medieval style forever and turning it into the capital of the new Kingdom of Italy (1865-70).

In May 1865, the monument to Dante was inaugurated in Piazza Santa Croce, with an impressive ceremony attended by King Victor Emmanuel II. The event was of nationwide importance as it was the first celebration for the Kingdom of Italy, and it was held in Florence since it was chosen as the capital of the Kingdom just a few months earlier. It was the first time that Dante’s birth was celebrated. “La Nazione” (the main local newspaper) reported the event on the 14th of May: “Today in Florence, after six centuries, Italy is celebrating the birth of Dante Alighieri”. (Extract from P. Aranguren, Le feste per il Centenario (1865) della nascita di Dante in Firenze capitale, from “La Martinella”, 1965).

Bibliography: G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’ suoi quartieri, Firenze, nella stamperia di Gaetano Viviani, 1754-1762, 10 voll.; La Toscane. Album monumental et pittoresque exécuté sous la direction de M. le Prince Anatole Démidoff, dessiné d’après nature par André Durand, avec la collaboration d’Eugène Ciceri, Paris, Lemercier, 1862 (ristampa anastatica, Firenze, Cassa di Risparmio, 1973); G. Carocci, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, 1897 (ristampa anastatica, Roma, Multigrafica, 1985); D. Tordi, Il padre Giuseppe Richa a San Giovannino e la stampa delle sue Notizie storiche sulle chiese fiorentine, estratto dagli “Atti della Società Colombaria”, Firenze, 1933; E. Pucci, Com’era Firenze 100 anni fa, Firenze Bonechi, 1969; P. Aranguren, Le feste per il Centenario (1865) della nascita di Dante in Firenze capitale, estratto da “La Martinella”, 1965; E. Detti, Firenze scomparsa, Firenze, Vallecchi, 1970”

Credits

Texts by Carla Basagni, Rino Cavasino, Francesco Marmorini, Daniela Nocentini, Silvia Tarchi, Rosario Ruggero Terrone.

Translations in English by Eurotrad snc; review by Giovanna Pecorilla.

Photographs by Roberto Palermo; editing by Lorenzo Cosentino and Patrizia Naldini.

Published October 2019