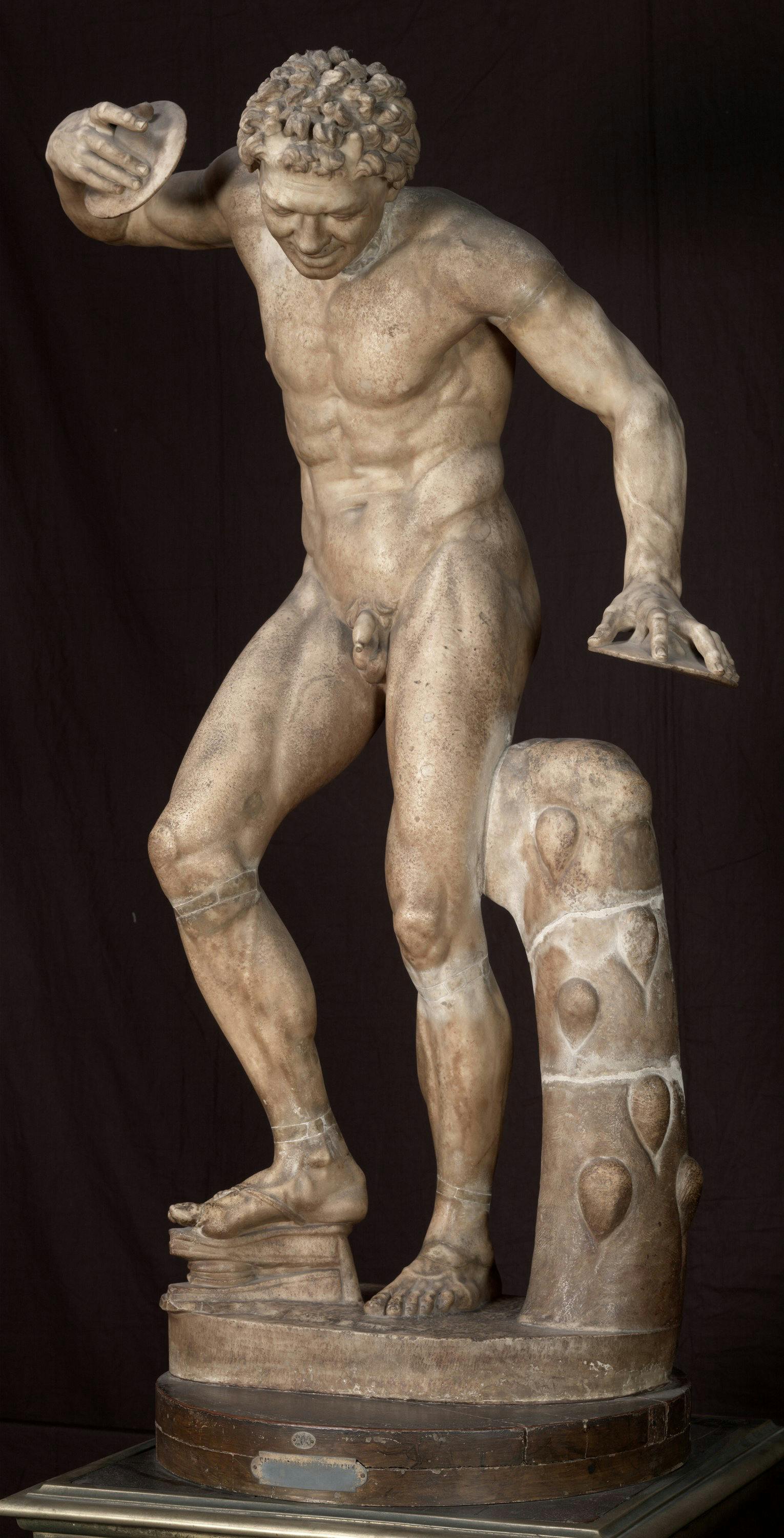

Dancing satyr (also known as kroupezeion)

Roman art

The sculpture depicts a satyr caught while performing a dance step, beating time with a foot castanet (kroupezeion in Greek). The ancient part of the sculpture comprises the body and the base, while the head and the arms, including the rattlesnake clasped in the right hand, are the result of a 16th-century addition. This splendid marble belonged to the collection of the Roman prelate Eurialo Silvestri (Ronchetti 2009), as it is also mentioned by Aldovrandi (1556 p. 278). After a brief passage at Villa Giulia, the marble was then purchased by the Medici family already at the end of the 16th century and brought to Florence in the early 17th century (Cecchi-Gasparri 2009 p. 388). In the last years of that century, it finally entered the Tribune to be included among the most famous sculptures of the Grand Duke's collection. The dancing satyr should ideally be completed with the figure of a seated nymph, so as to compose a group known as “the invitation to dance” (Ghisellini 2017). The Uffizi collections also contain a replica of the Seated Nymph (inv. 1914 No. 190), which is currently displayed in the second corridor. During the imperial age, the group was replicated several times to be used as a decoration of suburban villas and luxury residences, even though it was also found in thermal areas (Ghisellini 2017 pp. 65-66). To date, we have knowledge of thirty-one replicas of the satyr figure and thirty-eight of the nymph (Ghisellini 2017 pp. 77-70). With respect to the archetype, the great formal affinities with the small Pergamon donarium suggest that it should date back to the middle of the 2nd century B.C. (Meischner 2003 pp. 308-309). The fact that the group was depicted on the back side of coins minted in Cyzicus, Bithynia, led to the assumption that, even during the imperial age, the original piece used to be preserved in the ancient Greek colony overlooking the Sea of Marmara (Mosch 2007 pp. 115-118).

U. Aldovrandi, Delle statue antiche che per tutta Roma e in diversi luoghi e case particolari si veggono, Venezia 1556; F. Haskell – N. Penny, Taste and Antique. The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500-1900, New Haven – London 1981; J. Meischner, Die Skulpturen des Hatay Museums von Antakya, JdI 118 (2003), pp. 285-339; H. C. Mosch, Eine “Aufforderung zum Tanz” in Kyzikos und Pautalia. Der Beitrag der Münzen zum Verständnis eines hellenistischen Meisterwerk, JNG 57 (2007), pp. 91-125; A. Cecchi, C. Gasparri, La Villa Médicis, Le collezioni del cardinale Ferdinando, IV, I dipinti e le sculture, Roma 2009; E. Ronchetti, Sulla collezione di antichità di Eurialo Silvestri, Ricerche di Storia dell’Arte, 1/2009, pp. 77-87; E. Ghisellini, L’invito alla danza: osservazioni sulla tradizione copistica del gruppo in margine ad una testa inedita della ninfa nel Museo Nazionale Romano, Rivista di Archeologia, XLI (2017), pp. 61-80.

Seated nymph

Roman art

The Tribune

Bernardo Buontalenti ( Florence 1531 - 1608)